“Stories are sometimes better than doctors”

-Theodore Wesely Koch

Books can heal people.

They have the power to transport you to another world.

The words they contain can soothe, entertain, educate, and enlighten. Once you immerse yourself into the world unfolding in its pages, books have the power to offer solace, consolation, comfort, and above all hope.

To a mind riddled with confusion or uncertainty, books can offer clarity. To a person suffering from nerve-wracking anxiety, books can offer a healthy and much-needed distraction.

Sometimes when you can relate to the words of an author or a poet-someone you have never met- a connection is forged. You feel understood, validated, a little less alone in your experiences. Books can open your mind, dispel your sense of alienation, offer you new perspectives.

The therapeutic potential of books is best demonstrated during dark periods of history, where man’s mental resources are depleted and his resilience stretched to its limit, leading to a collective neurosis. World War I is one such example when modern human society was plunged into chaos and paranoia and man was forced to confront his worst adversary-man himself.

Millions of soldiers-battling the barely survivable trenches, the incessant shelling, the chemical gas attacks, and witnessing the pointless loss of lives day after day- were left shell-shocked.

One of the interventions which helped them to keep their bearings and hold on to their sanity in times that were largely insane was books.

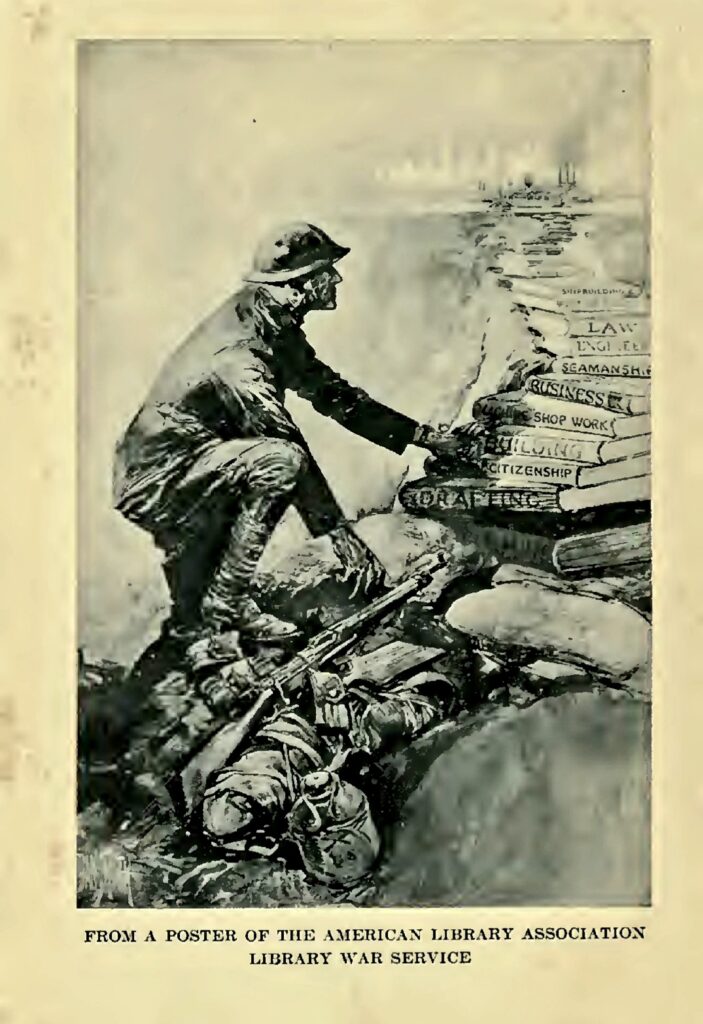

In the United States, during WWI, the Library of Congress in association with the American Library Association created the Library War Service. The Secretary of War chose 10 men and women librarians across the country who spearheaded a nationwide campaign to collect funds and books to create libraries in the soldiers’ camps and war hospitals. In its first wave of the campaign itself, they managed to procure 200,000 books.

Till the end of the war, a staggering number of 710 million books had been mobilized to 36 camp libraries and over 500 locations, solely for the soldiers fighting in the war, and recovering in hospitals from battle wounds. A similar campaign was soon underfoot in other nations such as Britain and France.

Many had reservations over this policy.

Will men in the camps read? Where will they find time for it?

These reservations dissipated soon enough, as the men forced to spend long hours in the camp, without any avenues for leisure or recreation, took to reading with unprecedented fervor.

One of the librarians noted:

“As they had little but the recreational halls to occupy their leisure, many who were not naturally studious were glad to turn to the libraries during the stormy days and long evenings.”

Many officers had to fervently write to the headquarters, asking for more books for their men.

The books made available in these libraries cut across genres and disciplines. The libraries had comprehensively curated collections of books on spirituality, fiction, poetry, language, vocational skills, history, travel, and so on. The aim was to entertain as well as educate these men herded together under unnatural conditions, waiting to plunge themselves into the throes of battle, from which they may or may not return alive.

Theodore Wesely Koch, a librarian who was instrumental in the Library War Service campaign and who wrote a book relating his experiences (Books in the War: The Romance of Library War Service ) wrote:

“The camp libraries…. helped to keep the men more fit physically, mentally, and spiritually, and prepared many for greater usefulness after the war. Good reading helped to keep many a soldier up to his highest level and aided in recovery of many a wounded man. It helped to keep him cheerful, and to send him back to the firing line with renewed determination to win or die bravely in the attempt.”

Books also became portals of escape for the battle-weary soldiers. While books of various genres were made available, librarians noted that fiction was preferred over non-fiction books with a ratio of 3:1.

Miriam E Carey, another librarian who recorded her observations in hospital libraries, noted that many soldiers recuperating in the war hospitals asked for romantic fiction-a choice most typically associated with women readers. In a paper presented later at an ALA conference, she hypothesized that the physically debilitating injuries caused by war were in a way an emasculating condition for these men. Although hardened by the constant fighting, they were also immensely homesick and craved for something nurturing and essentially feminine.

She wrote:

“… the doctors say that there is nothing really the matter with most of the sick soldiers, except sheer homesickness. What does a homesick man choose for his reading? Probably what he craves is an old-fashioned love story….. the man who is sick is more like his mother than his father.” (1918).

It was during this period that the science of bibliotherapy emerged as a psychological intervention that aims to alleviate mental health issues and promote mental well-being through reading books. The Library War Service stationed librarians in hospitals and they along with the doctors “prescribed” books to the soldiers to aid their physical and mental recovery. They were even provided with a uniform of their own, to put them at par with the medical and paramedical professionals.

While books in camps aimed to educate the soldiers about the war and enable them to acquire knowledge and vocational skills for post-war life, the hospital libraries played a therapeutic role. The librarians would talk to the soldiers at length, and in keeping with their desire for consolation or escape, prescribe books that would suit them best.

This therapeutic intervention of matching a book to a patient was not without its dilemmas: Was a healing book one that offered an escape from illness, or one that allowed a reader to confront it?

There was no easy answer to this question. Many patients suffering from debilitating anxiety found more comfort in a serious book than a light-hearted one. Many wished to avoid books with characters suffering a similar kind of illness as them, while others felt comforted by the same. It was a uniquely individual process and the “therapeutic librarians” found themselves learning on their job, the nuances of prescribing books to their patients.

But whatever be the choice of books, they made an unequivocal observation of the positive effects of books and reading in these soldiers. Books were instrumental in improving their mental wellness and reducing their anxiety.

Even though the American Library War Service of WW I brought to the forefront, the crucial role of books and reading to preserve the well-being of soldiers, this practice has been observed in history long before that. One of the earliest camp libraries, recorded in history was during Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt and comprised of over 1000 volumes with books on religion, poetry, history, and fiction.

Unfortunately, the interest in bibliotherapy lost steam in subsequent years, and libraries have not found a regular place in mental health services. However, they hold great promise in playing an adjuvant role alongside traditional interventions to help people deal with stress and mental suffering.

References:

Koch, T. W. (1919). Books in the war: the romance of Library War Service. Houghton Mifflin.

Miriam E. Carey. “What a Man Reads in Hospital.” The Library Journal 43, no. 8 (August 1918): 565-567.

Haslam, S., & King, E. G. (2021). ” Medicinable Literature”: Bibliotherapy, Literary Caregiving, and the First World War. Literature and Medicine, 39(2), 296-318.